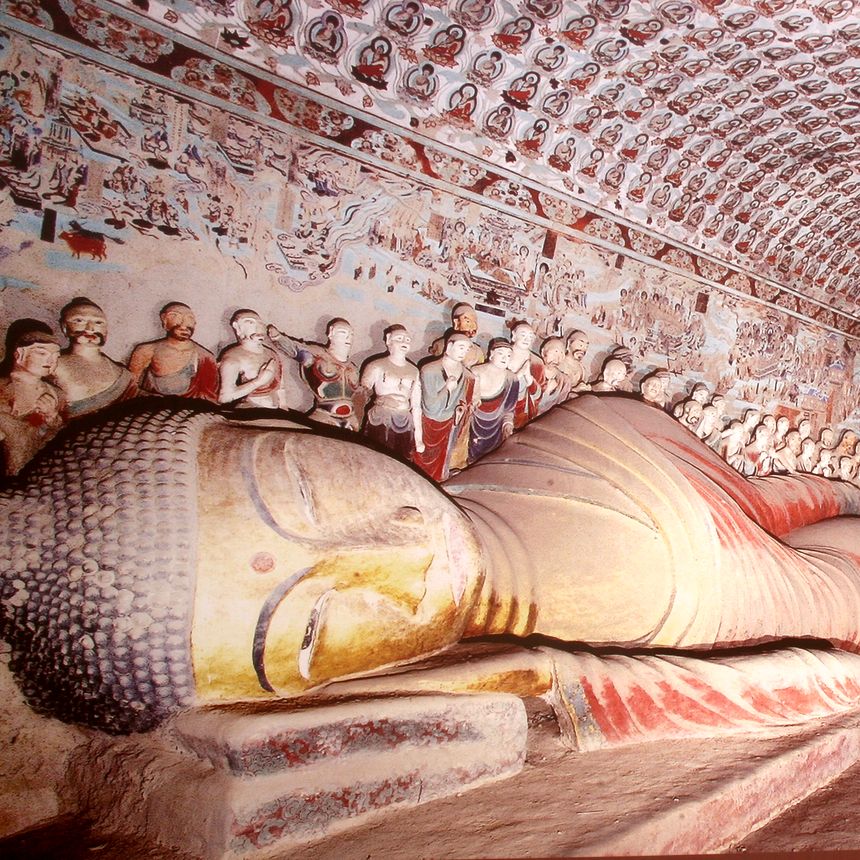

Silk Road through China

China

Silk Road | Culture

Trace ancient paths of merchants, scholars & smugglers

£4,085 pp

This is the per person group tour price, based on 2 sharing. The price is subject to change with exchange rate and flight cost fluctuations.

16 days